Hello! Today, I'd like to share an excerpt from a chapter of my master's thesis, focusing on how designers can effectively navigate and address errors in their visual translations.

Berzbach explains that translation errors can easily occur between designers and stakeholders. The latter often appear to designers like "aliens" speaking a different language: "The successful execution of a project is a communication task. [...] It will not succeed if you behave like a "Fachidiot" (german word for someone who is highly specialized in a specific field but lacks broader knowledge or perspective outside of that particular area) who only understands designers." (Berzbach, 2019, p. 120) Nevertheless, diversity is fundamentally good and should be appreciated. Conflicts can even give rise to new ideas. (cf. Berzbach, 2019, p. 70) As an outsider, one has the advantage of being able to objectively question the organization's existing beliefs and challenge them with alternative suggestions. However, if one is afraid of potential confrontation, this opportunity is missed, and everything remains as it is – sometimes to the advantage of a single powerful stakeholder and not for the benefit of end-users. (cf. Shea, 2012, p. 69)

In my case, there were individual team members who were reluctant to make significant changes to their existing logo. However, the majority felt not properly represented by it. So, I proposed an alternative and accepted that not everyone would be immediately enthusiastic about it.

One initial requirement for correcting a translation error is the ability to listen well. Ideally, this should occur on four different levels: The first level is called "Downloading," where we are on autopilot, seeking affirmations of existing assumptions. (cf. Mayer/Osann/Szymanski, 2021, Card: Generative Listening) On the second level, "factual listening," we verify the transmitted information for its accuracy. The third level, "empathic listening," helps to understand the emotional motivations of our counterpart. Within the fourth level, "generative listening," attention is focused on the future: How can what is heard contribute to progress and innovation? (cf. Mayer/Osann/Szymanski, 2021, Card: Generative Listening) For example, when the community leader told me that the new logo design was very different from the old one, empathic listening was crucial. It was not the design that was disliked but the change that caused fear.

In addition to listening, it can be useful to take notes. These can serve as anchors and allow for reflection after the conversation. If something is not understood, it is best to ask directly. This can help uncover any unsound criticism. Personally, I prefer to conduct conversations in writing via email or WhatsApp. It gives me time to formulate the response precisely, and the counterpart can also consider the information before replying. In my experience, this approach tends to lead to more thoughtful interactions for both parties.

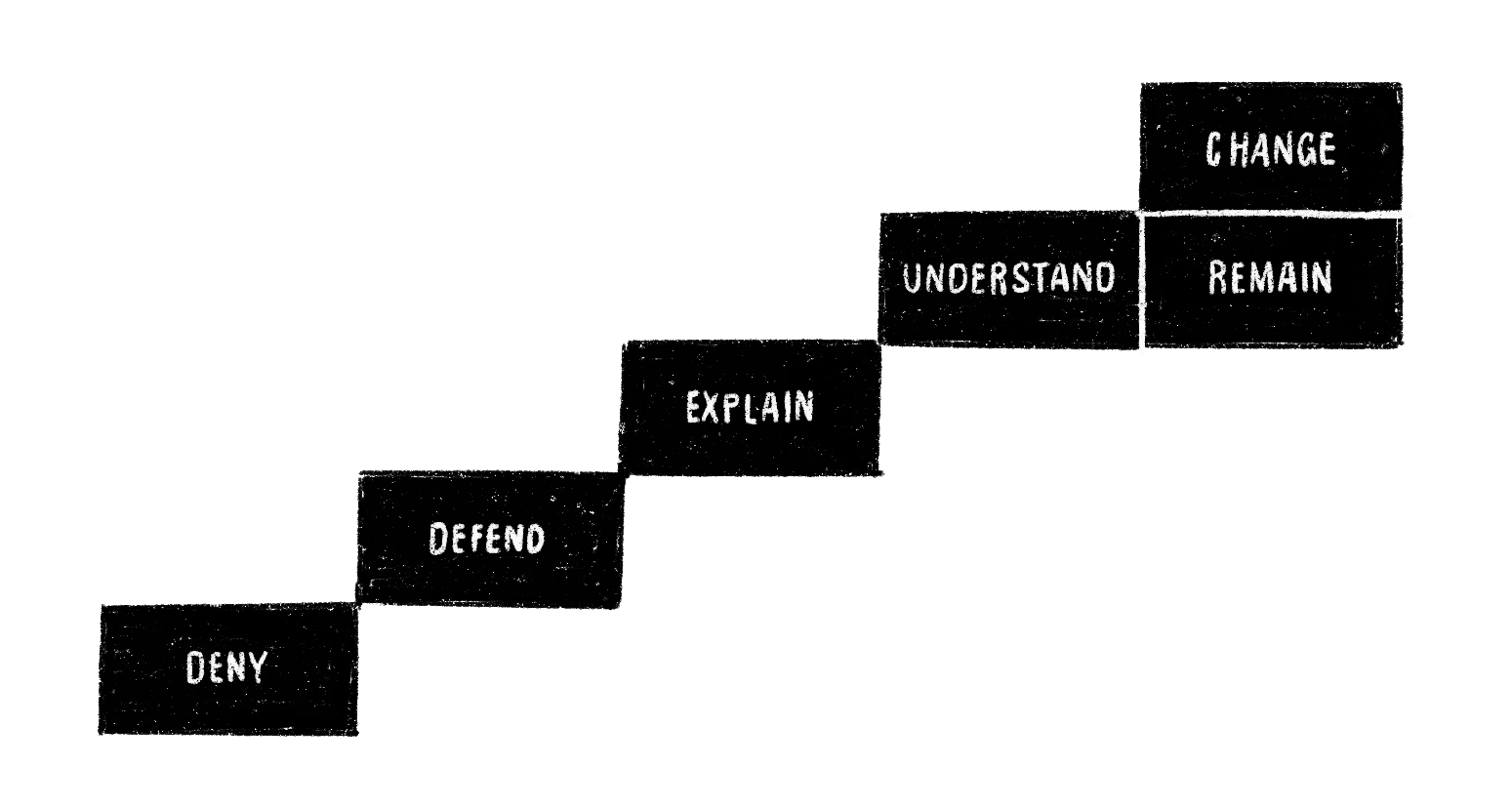

Berzbach adds: "Justifications or defenses are entirely unnecessary." (Berzbach, 2019, p. 37) As a good example, he mentions the "Gruppe 47," consisting of influential writers of the post-war era. During their meetings, authors were not allowed to respond immediately to group criticism of their texts – they were only supposed to listen first. This measure can help prevent thinking about the appropriate response while listening. (cf. ibid, p. 37) This concept is also illustrated by the "Feedback Stairs" The first stage is the "Denial" mode: The problem raised by the conversation partner is not recognized as a problem. The next stage is the "Defense" stage. A statement at this point might be, for example, "You just don't understand." The feedback is still being rejected. (cf. Mayer/Osann/Szymanski, 2021, Card: Accepting Feedback) The next step on the stage already involves an "Explanation." Here, the conversation partner's opinion is accepted, and it is explained why a particular decision was made. The two final stages consist of "Understanding" and "Changing" and describe the ideal response to feedback. (cf. ibid)

Sometimes it can happen that it is simply not possible to climb the feedback steps. In such situations, designers may end up perceiving themselves as "the good guys" and others as "the villains" (Berzbach, 2019, p. 71) . This is quite human; conflicts lead to hypersensitivity, making it difficult to empathize with the other party in this state. In such cases, postponing the argument to the next day can be helpful (cf. ibid, p. 71f.) .

To prevent reaching such a point in the first place, it should always be clear that feedback relates to a design, idea, or concept, not the designers as individuals. This realization is facilitated when feedback is formulated as concretely as possible from the first-person perspective and is accompanied by an explanation. For instance, instead of saying "Green doesn't work at all!" it's more helpful to say something like "When I think of green, I associate it with nature" (cf. ibid, p. 34–36) .

For example, I was puzzled why the team insisted on sticking with one specific color, even though initially, all stakeholders provided feedback that they didn't identify this color with their vision. During the conversation, I discovered the argument that the work jackets were this hue. I assured them that this wouldn't be an issue and that we could customize them with embroidery or buttons.

Drew de Soto recommends asking the following questions when stakeholders don't provide understandable explanations: "What are you trying to achieve?" and "What exactly is the problem with the current design?" The goal of these questions is to encourage them to explain the problem first before suggesting design solutions (cf. Soto, 2019, p. 64) .

This may initially seem contradictory to the idea of participatory design, but at this point, it's worth recalling Drain and Sanders, who assume that both designers and non-designers carry essential knowledge for collaboration. Non-designers bring "silent knowledge" about their socio-cultural environment, everyday life, and specific desires and needs. Designers, on the other hand, contribute experiences related to the design process, project management, and technical knowledge (cf. Drain, Andrew/Sanders, Elizabeth B. -N., 2019, p. 39f.) . This could mean that designers should encourage stakeholders to express their feedback in a way that brings their "silent knowledge" to light, which designers can then use in collaboration with their technical strengths and experience in the design process. Nevertheless, I experimented with the mentioned color variations that the team wanted to see in connection with their logo. In the end, they still chose the initial version.

"Iteration is the name of the game in human-centered design," says IDEO. This means continually improving the design step by step. If designers identify with this mindset, rather than believing that the first draft must be perfect, it becomes easier to handle feedback since it supports the process of correction and optimization (cf. IDEO, 2015, p. 25). Annie Kerguenne states, "Experimenting forward is the driver to evolution and excellence." Nowadays, we face problems that lack predefined solutions. Design tasks are more like a labyrinth than a roadmap. Examples include top chefs, medal winners, but also all children who have grown into adults. Since they came into this world, they have learned a lot through trial and error, making them the individuals they are now (cf. Kerguenne, n.d., online) . Within the iteration process, Soto recommends that designers give stakeholders enough time to get used to the new design. When they assigned the task, they likely already had something in mind. "You can be 100 per cent sure that what you have shown them will not be what they are expecting. So, it will take time and an explanation" (Soto, 2014, p. 168).

Sources:

Berzbach, Frank: Kreativität aushalten/Psychologie für Designer. 6. Aufl. Mainz: Verlag Hermann Schmidt 2019

Shea, Andrew: Designing for social change: Strategies for community-based graphic design. New York: Princeton Architectural Press 2012

Mayer, Lena/Osann, Isabell/Szymanski, Caroline: Design Thinking Navigator: Das Kartenset zur kreativen Projektarbeit. München: Carl Hanser Verlag GmbhH & Co.KG 2021

Soto, Drew: Know your Onions: Corporate Identity: Get your head around corporate identity design and deliver one like the big boys and girls. Amsterdam: BIS Publisher 2019

Drain, Andrew/Sanders, Elizabeth B. -N. (2019). A collaboration system model for planning and evaluating participatory design projects. International Journal of Design, 13(3), 39-52.

IDEO U (12.06.2019) What are Essential Collaborative Behaviors? o.O. 2019. In: Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Igb1NUV_kr0 (last accessed on 28.09.2023)

Kerguenne, Annie: Experimenting Forward. Inspirations for Design: A Course on Human-Centered Research. In: Open HPI, https://open.hpi.de/courses/insights-2017/items/3TuLe1Xs0pdul0hqTqJDAw (last accessed on 26.09.2023)

Cover Picture:

Feedback-Ladder

Ilustrated by me, in reference to: Murphy, Ant (27.05.2019) How to Master Yourself and Win at Receiving Feedback.

In: Medium, https://medium.com/the-ascent/how-to-master-yourself-and-win-at-receiving-feedback-b1dc757d02fe (last accessed on: 29.10.2023)

No comments.